By: Surbhi Mahajan

Comoros’ electoral body declared incumbent President Azali Assoumani winner of the country’s presidential elections with 60.8 percent of the vote. Opposition and rights organisations, including observers from African union claim the voting was a sham, lack of transparency, there was widespread violence and crackdown on political opposition. Azali has been accused of employing increasingly authoritarian tactics in the past.

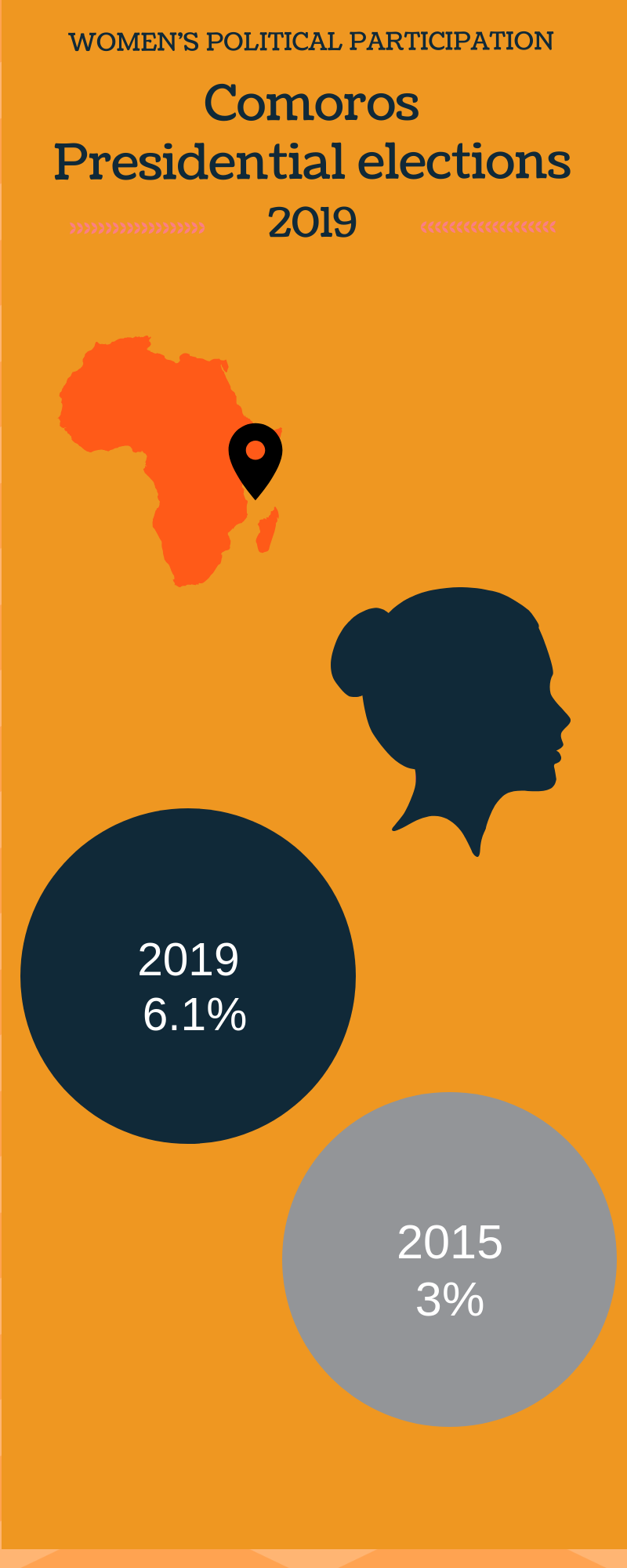

Women’s Political Participation

The Constitution, which was last modified in 2009, guarantees several positive legislations in favour of women’s rights; with women gaining the right to stand for elections back in 1956. However, it was not until 1992 that the first women ran for public office at the national level. At the same time, the Constitution while recognising the equality of all in rights and duties without distinction of sex, origin, race, religion or belief (Preamble), does not really recognise and prohibit multiple or intersectional discrimination.

In terms of women presence in top political leadership positions, from 12 women running for office in 1992 (none elected), to 9 in 1993 (1 elected), to 50 women candidates for legislative office during 2009 elections, women’s equal representation and participation has been rather abysmal. Between 2010 and 2016, one woman was serving in the 33-member parliament, making up 3% of the total. In 2017, a second woman joined parliament, doubling representation to 6.1%. Moreover, there are no female ministers, even though in the past few years women have served in the President’s cabinet as ministers of Employment, Labour, Vocation Training and Women’s Entrepreneurship and Telecommunications. For the years that data were available, women comprised 30% of the Cabinet in 2010, and 20% in 2012, 2015, and 2016. Currently, number of female parliamentarians remains two post-2019 elections. In fact, no female candidates even contested this time around. Adding to this, Comoros does not have gender quotas. If a legislation is passed it would be a crucial and important step towards correcting the gender imbalance in political representation.

As far as local elections are concerned, recent data between 2015-16 suggests, around 5.4% women ran for position of Counsel; 4.5% for Governors; and 3.7% for President.

Coming to laws promoting and guaranteeing gender equality in the country, Comoros ratified the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1994 and is one of three majority Islamic States to have signed the agreement with no reservations. The country ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2004. Rape is punishable by law with a maximum sentence of fifteen years if the victim is under the age of fifteen. A law was passed in 2014 to increase the punishment for rape as well as to criminalise spousal rape.

On the whole, a real lack of State’s commitment to address or rectify power inequities that have disadvantaged women all this while is evidently visible. Moreover, several other barriers continue to adversely affect women’s participation at any level: from institutional barriers in the form of no gender quotas and lack of training infrastructure to financial constraints while contesting elections. A deposit of $1,200 is needed and only reimbursed to candidates who win at least 10% of the votes. The socio-cultural barriers also continue to persist and reproduce gender stereotypes of women’s roles and responsibilities.

Conclusion

Comoros remains one of the few countries where access to equal representation in politics remains a huge challenge. This brings us to the question of addressing structural inequalities and how to enhance pathways that will ensure not only increased presence in Parliaments but also the quality of leadership.