Zimbabwe saw its presidential poll action on July 30, 2018. Emmerson Mnangagwa won 50.8% of the vote in what is deemed as Zimbabwe's historic first election since the fall of Robert Mugabe. There were 23 presidential candidates of which 4 were women. They included Mujuru Joice of People's Rainbow Coalition, Khupe Thokozani of MDC-T, Mariyacha Violet of United Democratic Movement and Dzapasi Melbah of 1980 Freedom Movement Zimbabwe. Observers like the European Union and rights’ groups have questioned the heavy-handedness of the manner in which the elections were conducted. Opposition leaders have called it a ‘coup against [the people's] will.’

Women’s Political Participation

Zimbabwe is a signatory to many declarations aimed at increasing women leadership and decision-making such as the Maputo Protocol (signed in 2003 and ratified in 2008), Southern Africa Development Committee (SADC) Gender Protocol on Gender and Development of 1997, Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) 1979 and the Beijing Platform for Action of 1995.

Zimbabwe’s constitution, that came into effect in 2013, guarantees a positive and robust legislation in favour of women’s rights. On the political participation front, it observes that the State must take all measures so that – “both genders are equally represented in all institutions and agencies of government at every level; and women constitute at least half the membership of all Commissions and other elective and appointed governmental bodies established by or under this Constitution or any Act of Parliament.” 60 additional seats were reserved for women for proportional representation. However, the quota expires in 2023 and it also does not extend to local government, which is currently at 15%. Furthermore, there are no explicit provisions to include young women in the public sphere. In fact, an extension of the quota at national level beyond 2023, with the Women in Local Government Forum calling for the quota to be extended to local government as well, has become the major focus of women’s rights groups and Zimbabwe women’s parliamentary caucus in partnership with civil society.

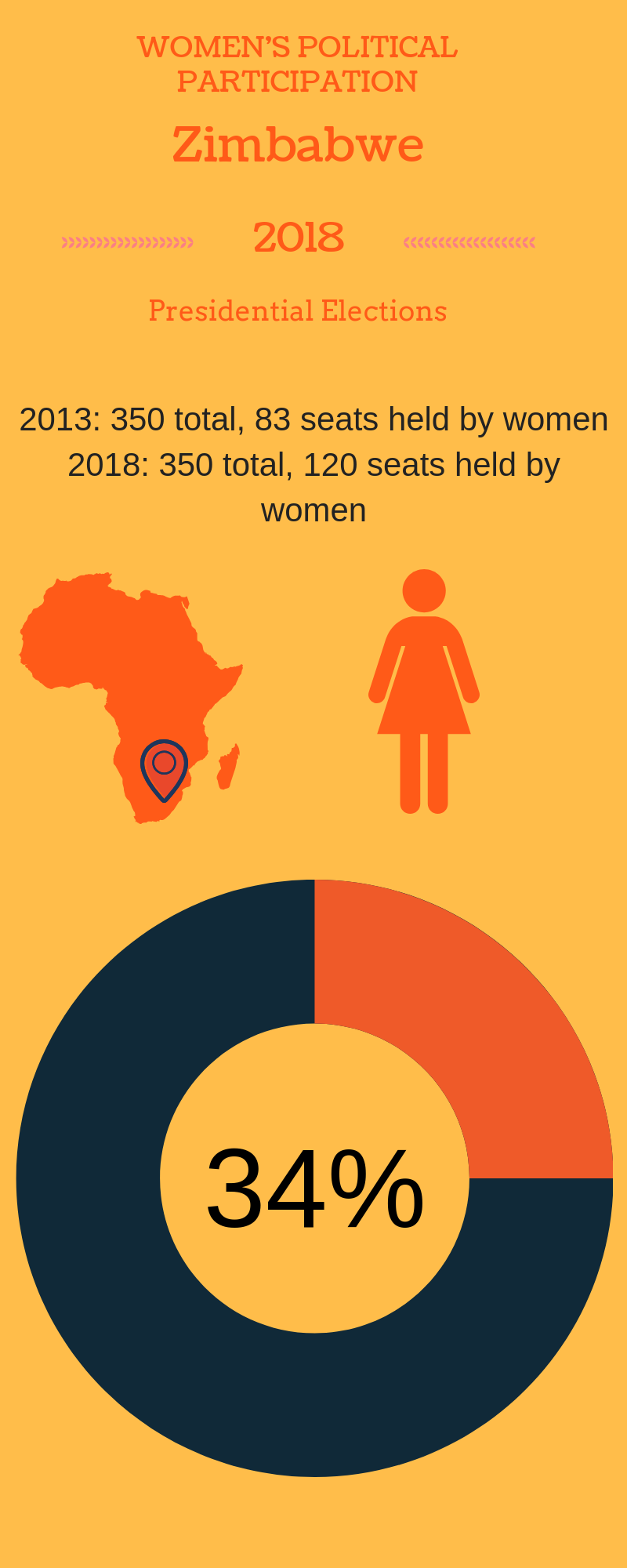

Recent presidential election saw 120 of total 350 seats, in both houses, occupied by women, which means 34% of women politicians currently are present in the parliament, which is a significant increase from 23% and 15% in 2013 and 2008 respectively. However, their overall participation in electoral and governance processes remains peripheral.

Firstly, all political parties performed dismally with regards to fielding female candidates. The election also saw a repeat pattern of violence and intimidation of both women voters and candidates, as noted by the Zimbabwe Gender Commission, which is a major contributing factor with regards to women’s “failure” to make a significant impact. For instance, young unmarried women such as independent candidate Fadzayi Mahere and aspirant MP Linda Masarira, faced sexist backlash and bullying statements from men about their eligibility to be politicians, given their ‘lack of husbands’. This is reflective of a deeply patriarchal mind-set and hostile environment in which they have to function.

Having said that, there is some semblance of an enabling legal framework in place, which at least attempts to highlight the concept of gender equality in Zimbabwe. The constitutional provisions recognise and guarantee protection of women’s rights as equal citizens and the right to life of dignity. From establishing institutions like the Gender Commissions to bringing in laws like Domestic Violence Act 2006, the government is assuming responsibility to ensure women are protected from violence. Harmful cultural practices like nhaka and kuzvarira that discriminate against or cause harm to women are prohibited by Section 78(1). Both the Marriage Act and the customary marriage practices are seen as infringements on women and girls’ rights. Section 80(2) provides that women now have the same rights as men regarding custody and guardianship of children.

Conclusion

Despite the relative progress made, access to equal representation in politics remains a huge challenge. Little resources, political violence, and patriarchal practices, coupled with lack of political will and larger gender awareness, continue to deliberately invisiblise women. This brings us to the question of addressing gender inequalities and how to enhance pathways that will ensure not only increased presence in Parliaments and local governance, but also quality of leadership.